S7. E21: Carter Niemeyer: Wolfer

“Packs that are continuously trapped and snared and hunted, the packs are smaller and things are a lot more chaotic in the pack because you're killing uncle, you're killing dad, you're killing mom. The pups may get good leadership training and learn how to hunt or the family could be broken up and the puppies never fully learn how to hunt.

“And so all this hunting and trapping lowers the pack size, fragments them often and might cause a pack to break up, and those broken packs can actually send out more wolves in more places.

“So, all this intense wolf killing, in my opinion, it's not justified and it's unnecessary because what it's creating now, instead of biological carrying capacity, they're managed politically on social carrying capacity. How many wolves will people tolerate?”

- Carter Niemeyer

This is the second episode in a series that will hopefully get more of us to care about wolves and then do something to stop the current slaughter spree before it's too late.

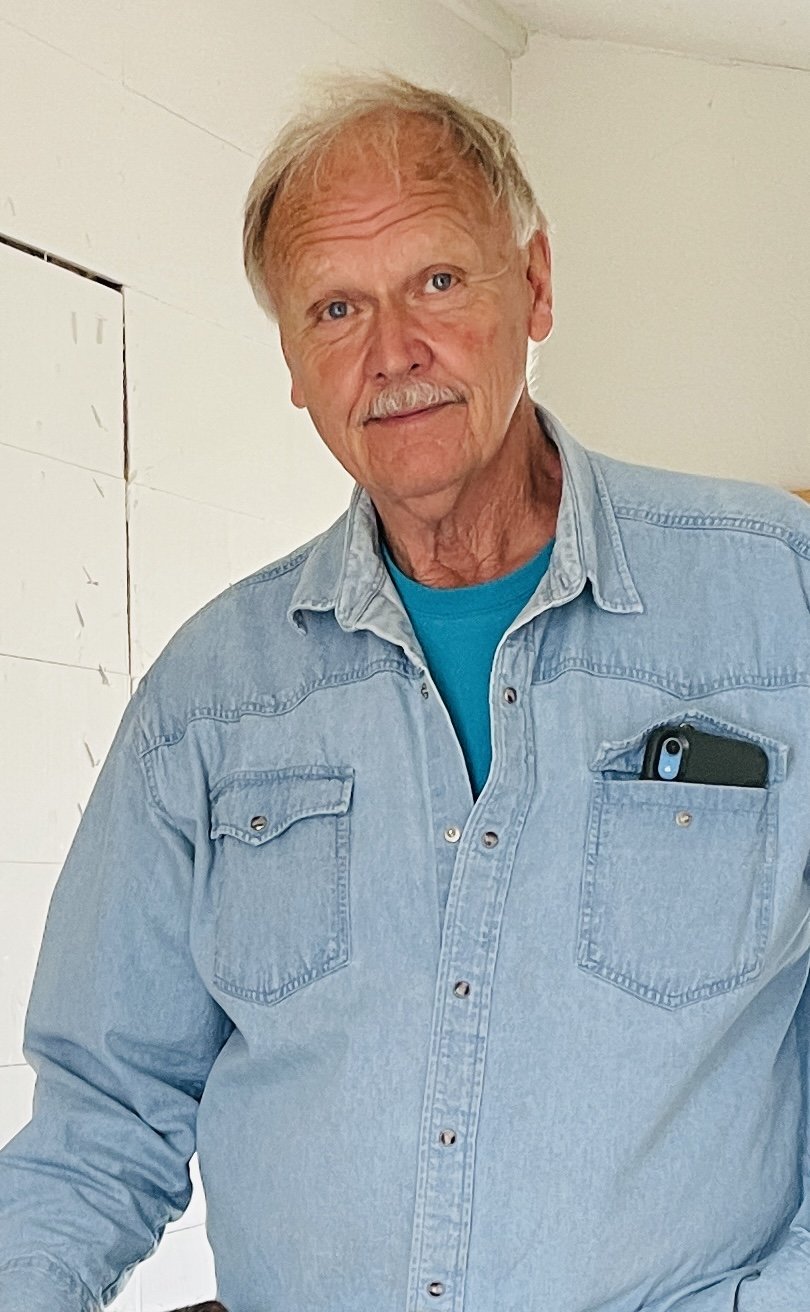

Carter Niemeyer is a wildlife biologist who has been working with wolves since the 1980s. After decades as a trapper of wolves (and many other predators) he transformed into one of their biggest champions.

He worked as a state trapper and conducted wildlife studies for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and by 1990, he was a full-time wolf specialist, negotiating situations where wolves were in conflict with people.

In the mid ‘90s, he became a core member of the Wolf Capture Team in Canada. They were there to capture and bring wolves back to the U.S. for the Federal Wolf Reintroduction Program.

Carter’s stories are seriously astonishing and span more than five decades of work with large predators. He’s been a naturalist since he could walk and his love of nature and the outdoors are at the core of his very being.

I spent the afternoon with him at his house in Idaho. I wanted to better understand the wolf hatred and hysteria that’s been going in Idaho, Wyoming and Montana for centuries - but currently seems to be at an all-time high.

I wanted to hear Carter’s perspective, the thoughts of a former trapper on the wolf massacre that’s taking place today in the Northern Rockies and to ask him if there’s anything that we can do to stop it.

Please listen and share.

In gratitude,

Elizabeth Novogratz

Learn more about Carter

Transcript:

Carter: [00:00:11] Packs that are continuously trapped and snared and hunted. The packs are smaller. Things are a lot more chaotic in the pack because you're killing your uncle. You're killing dad, you're killing mom. The pups may get good leadership training and learn how to hunt, or the family could be broken up and the puppies never fully learn how to hunt. So all this hunting, trapping and things lower, the pack size fragmenting them often might cause a pack to break up, and those broken packs can actually send out more wolves and more places. So all this intense wolf killing, in my opinion, it's not justified and it's unnecessary because what it's creating now, instead of biological carrying capacity, they're managed politically on social carrying capacity. How many wolves will people tolerate?

Elizabeth: [00:01:17] Hi. I'm Elizabeth Novogratz. This is a Species Unite. We have a favor to ask. If you like today's episode and you have a spare minute, could you please rate and review Species Unite on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts? It really helps people to find the show. This conversation is with Carter Niemeyer. Carter is a wildlife biologist who has been working with wolves since the 1980s, and throughout that time he transformed from a trapper to a champion of wolves. He worked as a state trapper and conducted wildlife studies for US Fish and Wildlife, and by 1990 he was a full time wolf specialist, meaning he negotiated situations where wolves were in conflict with people. Then in the mid nineties, he became a member of the Wolf Captured team in Canada. These were the guys that went to Canada to capture wolves and bring them back to the US for the Federal Wolf Reintroduction Program. This was a time in the US where wolves were almost totally extinct and this was how we got them back. Carter has five decade's worth of seriously astonishing stories of working with large predators and his love for nature and the outdoors, and mostly his love for wolves. I spent the afternoon with him at his house in Idaho. I wanted to better understand the wolf hatred and hysteria that's currently happening there, as well as in Wyoming and Montana. Carter, thank you so much for inviting me to your house. It's awesome to be here and it's just really cool to meet you in person.

Carter: [00:03:09] You're very welcome. It's my pleasure to get to visit with you.

Elizabeth: [00:03:13] We're going to get into all things wolves, and that is the main reason that I'm here, because so many bad things are happening right now with wolves and have been for years, but it's worse than it's ever been. You've been in this literally since the very beginning with the wolves and before that with a lot of other predators and before that with other animals. So just to kind of set us up and get a bigger picture of your life, will you talk a little bit about growing up in Iowa and how this all started?

Carter: [00:03:43] Well, I've been an outdoor person since my most distant memory. I'm serious, but it sounds like a joke sometimes. But I was out in my diaper wandering off in the corn stubble fields when I was just like two or three years old and had my little walking stick. Sometimes I had my little pantaloons on and I was always out poking at bees with a stick or a spoon and getting stung and coming home, going in the house crying. We had dogs, always had dogs. So I followed them as I was getting bigger and older. I grew up on the edge of Garner, Iowa, which was right on the east edge of the town and immediately across the road, it became rural. It was cornfields and oat fields, and you could go for miles and others in a few farmhouses. There's just nothing out there but more fields, those fields were full of rabbits and pheasants and partridge and everything imaginable out there.

Elizabeth: [00:04:52] You're kind of a naturalist, you've been training your whole life?

Carter: [00:04:55] Right? Yeah, it was something I became so enamored and familiar with that I didn't know anything else. So it just perked my curiosity and is kind of what I knew.

Elizabeth: [00:05:08] Did you know that this was your path and where you were going?

Carter: [00:05:11] Well, not really, but I can't imagine what else I'd do other than be a wildlife biologist. That's all I would ever care to do. So that's the profession I chose. After I graduated, the school came back and said, Well, since you're quite an avid and successful hunter and trapper, we're looking for a graduate student to do a rabies study in striped skunks. Then I got a call from Montana. To ask if I was interested in coming out there because of the experience I had with rabies and skunks and my college training. So, unbelievably, I got the call on a Thursday accepted on a Friday. Moved everything. I just been married a couple of years ago.

Elizabeth: [00:05:59] Had you been in Iowa your whole life at this point?

Carter: [00:06:00] I had been, yes.

Elizabeth: [00:06:02] That's a big move. I mean, it's a lot different.

Carter: [00:06:04] Well, it was very abnormal for me because my family in Iowa didn't go anywhere. I mean, everybody. Born, raised, lived and died almost in the same town. My brother was a teacher and he moved to another town in Iowa. So it was very. Abnormal, I think, for me too. I really didn't even hardly know where Montana was on a map at the time.

Elizabeth: [00:06:33] This was all scary.

Carter: [00:06:34] Well, it was in. So four days after the call, I moved everything I own into my father in law's garage, left my wife behind and hopped an Amtrak train in Minneapolis. Not knowing anything about what my future would bring, I landed in a town called Wolf Point, Montana.

Elizabeth: [00:07:01] Wow.

Carter: [00:07:03] Yeah.

Elizabeth: [00:07:04] That is awesome.

Carter: [00:07:06] That's where the guy that hired me met me at the train station in Wolf Point, Montana. I was just dazzled with the country. It was kind of like Little House on the Prairie type design, big endless miles of rolling hills with wheat or just prairie grass. We drove and drove and drove and took me to a little town called Plenty Wood, Montana, which is ironic because there's almost no trees in Plenty Wood. So it was whether they named it and said, bring plenty of wood when you come, I don't know. But it was roughly, I believe, 17 miles from Saskatchewan, Canada and ten miles from the North Dakota border. So way up in the very northeast corner of the state of Montana.

Elizabeth: [00:07:57] You had a reputation as a trapper and hunter, Did a lot of wildlife biologists have reputations as trappers and hunters at the time?

Carter: [00:08:07] I would call myself a professional trapper. By the time I went to Montana, I trapped as a kid and a teenager and I paid my way. Basically helped pay my way through college at Iowa State as a trapper, trapping fox, trapping mink and muskrats and different critters.

Elizabeth: [00:08:27] Who would you sell them to?

Carter: [00:08:29] Fur buyers. I would fix up animal pelts that were damaged from gunshots. Wash them, skin the animal, wash them in a washing machine and sew up the bullet holes and comb out the damage that you would never know the animal had been shot. Fur buyers paid me nice money to do that too. So I had all that familiarity with the fur handling industry too. So that year I did the rabies suppression project. It ended. I noticed while working there, there was just a tremendous red fox population and coyotes in northeast Montana. The job ran out. Here I sat out in Montana, out of work. I decided, well, I can trap for the winter. So I stayed out there and started trapping in September and stayed out there till Christmas time and put my fox pelts in a big couple of big boxes and put them on the train and shipped them back to Minneapolis with me. But I caught 400 foxes in about a month and a half, two months of trapping out there. Then my daughter was born before I could get back and she had a birth defect that required serious surgery. I made about 30 bucks a piece on those foxes times 400. It just covered the bill because I didn't have insurance. So I paid all my fur money to Rochester, Minnesota, but got my daughter through her health crisis. So the fur thing had been and it was an important thing to me at that time. Then a mentor, friend of mine who had actually helped convince people that maybe they should hire me when I graduated from Iowa State. He called me and he said, Hey, I've got a project at Mile City, Montana. He was a US Fish and Wildlife Service biologist. He said, Why don't you come over and work for me? So I moved my wife and daughter and I went over to Miles City, Montana, and lived in a fish hatchery house there. I did wildlife surveys, all kinds that I actually started. He wanted me to trap and put collars on bobcats, so I trapped bobcats and put radio collars on them and flew in an airplane and radio track. The Bobcats, which lived kind of the tongue river drainage south of Mile City.

Elizabeth: [00:11:17] I've read about this in your books, but when you trap, like when you're trapping and releasing, you try to basically just get like a little bit of their foot so they don't get hurt. Really, right?

Carter: [00:11:28] Yeah. Thanks for clarifying, because all this is kind of a matter of fact to me and I forget the details sometimes. But yeah, I go down, scout around, find where the bobcats were. Bobcats have toilets, kind of like a house cat does. So you find where the cats walk, where their toilets are. Then I would set foot hole traps, conceal them and check them early every morning and you'd have them by a pour. Then I used a chemical immobilization method. Ketamine is what the drug was. So yeah, you inject the bobcat to sedate and they're easy to handle.

Elizabeth: [00:12:10] So getting from when their foot's in the trap, the paws and the trap to get in the ketamine and the mouse. How does that go?

Carter: [00:12:18] Okay. Well, you use what I call a syringe pole. It's got a regular syringe that everyone's used to doing hand injections, except this has a long handle so that you can reach.

Elizabeth: [00:12:33] Without them reaching you.

Carter: [00:12:34] Exactly. Sometimes they try to reach you anyway because they're very excited and want to tear someone apart if they can get hold of you. But I've never really ever had that problem with an animal getting a hold of me. See once you get that. In that case, ketamine in them, they calm down, take the trap off immediately. If you check them early in the morning, those traps really don't hurt their paws. So then you take blood samples and put in an ear tag in the cat and then put a collar and fit it on them and let them recover. Within days they're going about their business with the collar on. So we kind of kept track of what the Bobcats were doing, what they were eating, and what their territory's size was. Then I was looking at prairie falcons in the sandstone cliffs to the west of that tongue river country.

Elizabeth: [00:13:43] This whole time now you're working for Fish and Wildlife?

Carter: [00:13:46] Yeah, I'm working for the US Fish and Wildlife Service and all of that wildlife study was in relation to the they were developing the coal industry out there at the time. So I did that for my friend Bob. Then at the same time the US Fish and Wildlife Service had a branch of predator control and these guys were professional predator hunters, especially coyotes. So there they were government trappers in Mile City, trapping coyotes flying in fixed wing aircraft, piper cubs and aerial gunning them. I got acquainted with these guys and then a good friend of mine who taught me to trap in Iowa. He had moved out to Montana and was working for that same organization. It was called Animal Damage Control then. So I'd go down and get acquainted with these government trappers, and in the fall they would save the pelts for the government and sell the fur and the fur would go into a fund that would buy aviation fuel for the airplanes and helicopters to go out and shoot more coyotes. I demonstrated my ability to skin coyotes for them in this little building. They were fascinated that I had this skill. So, I go down there and we would all these men would be all skinning coyotes and the whole building would almost be ready to collapse from everybody tugging and pulling and so anyway, they pass the word up to their bosses that, hey, this guy with a wildlife degree is over here and he knows his business, knows how to kill coyotes, and he knows how to skin them. So then this director of animal damage control contacted me one day and he said, Hey, we're looking for someone to move to Dillon, Montana, and catch Golden Eagles for us. Which I had never done before.

Elizabeth: [00:15:51] Will you just explain what Golden Eagles do?

Carter: [00:15:53] They kill with their talons and they fly in and strike the animal. The talons are, I guess, inch and a half, two inches long and cause deep hemorrhage, muscle tissue damage. But they eventually can kill a full sized deer antelope. But they also get into domestic livestock like domestic sheep and do the same thing. The reason they wanted me to trap Golden Eagles was so they had to get him alive. Then every 15 or so eagles we caught, my boss would come from Billings with a flatbed trailer, and we'd put them all in these individual boxes and relocate them to other areas. Where they weren't around domestic sheep.

Elizabeth: [00:16:44] Okay. Okay.

Carter: [00:16:45] I should back up and say that the year they hired me, the University of Montana, where you're familiar with, they had necropsy, which is an animal autopsy necropsy, lambs from this ranch to determine that eagles were killing them and estimated that Golden Eagles were killing about $38,000 worth of lambs a year for these sheep producers.

Elizabeth: [00:17:13] Wow.

Carter: [00:17:14] Final count. My partner and I caught 142 golden eagles that spring in that region, which is about a township maybe six miles by six miles square. So then fast forwarding, I did that along with I was involved in all aspects of predator control with each of these trappers. For 16 years. I was the technical team mate to the trappers. They would call me when we had a grizzly bear problem, usually killing sheep, but sometimes calves. Breaking into buildings, whatever. So we would work together and set foot snares for this grizzly and catch them. Then I was the dark guy because I had the technical expertise to use the immobilizing drugs.

Elizabeth: [00:18:05] You had the long thing again with?

Carter: [00:18:07] You know, with grizzly bears. No. You use a dart gun because those are.

Elizabeth: [00:18:12] You do that.

Carter: [00:18:14] Yeah. Those were challenging, frightening and risky. Because you have this grizzly bear and a foot snare made of cable, a quarter inch cable, and we put them together ourselves. We were the ones who tightened the nuts on the cable clamps and when you had this grizzly bear and they'd often charge at you when they're caught in the snare and you always hope that you remembered to tighten everything.

Elizabeth: [00:18:46] I mean, that is terrifying.

Carter: [00:18:48] It's not so terrifying. It's just if you did everything right, nothing should go wrong. Youu always assume it's not going to go wrong. But you always have rifles, shotguns and backup weapons present. But all those years, 16 years of catching problem grizzlies, none hurt me or any of the people I worked with. We were able to do our job professionally.

Elizabeth: [00:19:16] They were all relocated?

Carter: [00:19:18] We never killed any of the Grizzlies, except with one exception. One time we shot and killed a grizzly bear that had been caught in foot snares so many times that you couldn't catch it. It wouldn't go in them, but it kept killing sheep. We finally got what they called a kill order that that bear has to be stopped. So we put up a tree stand at night with a spotlight and we're able to fool it and kill that one. But yeah, all the other grizzlies, we hauled them to three mountain ranges away and released them in places where they weren't domestic sheep and hoped they didn't come back. Several did. It's amazing the homing instincts that animals, whether you're talking about golden eagles or grizzly bears, can find their way home sometimes very rapidly. Over tremendous distances.

Elizabeth: [00:20:17] So when did wolves enter the scene?

Carter: [00:20:19] Wolves started coming into Montana in the mid 1980s, up around Glacier National Park.

Elizabeth: [00:20:26] From Canada?

Carter: [00:20:27] From yeah, these were from Canada. Wolves and human beings are about the two most widely distributed land mammals on earth in North America and most of the rest of the world. With European settlement starting mostly from the east, going west. Human settlement encountered deer, elk, moose, wolves, grizzly bears, all of the species that roam this country, including millions of bison. The pioneers met these animals. They killed them to eat. They killed them to protect their stock. Then gradually, they became commercially killed for market hunters. Wasteful, but collecting buffalo hides and tongues, by the turn of the century in 1900, a lot of these species were on their way out. Could have gone extinct if people didn't wake up and realize that we just can't keep doing this.

Elizabeth: [00:21:41] Kind of like now.

Carter: [00:21:43] Yeah. Because even today, when you think about it, you look at the country where there aren't grain fields, corn fields, soybean fields, where aren't there cows and cattle grazing and sheep grazing? When the rural fields are full of crops or livestock, everything else now is becoming subdivisions, urban sprawls and warehouses. People think about wherever you live. Just think about what's happened in the last 50 years. Every square inch of ground is spoken for. Somebody owns or possesses it, except mainly in the western United States, 11 Western states. We have tremendous numbers. Millions of acres of public land. That belongs to all of us, everybody in this country.

Elizabeth: [00:22:47] I don't think people realize that we really have nothing left and what are we doing to the public lands? We're putting a bunch of cattle on them.

Carter: [00:22:54] Millions of acres are used every summer for public land grazing where ranchers can take their cows and calves, sheep and lambs put them on the public lands for about four or five months each summer. They pay a dollar 35 per UM which is dirt cheap grazing and AUM was a unit that would support a cow in her calf for a month or five sheep and their five lambs.

Elizabeth: [00:23:28] $1.35?

Carter: [00:23:30] $1.35. If you check around on the AUM’s as you get back in the Midwest and Eastern United States, livestock growers there might lease or rent property from their neighbor $40 per UM or more, and they have to compete in the same markets, selling the cattle. So out west here, buck 35 is very cheap and it's been political many times that they've tried to raise that buck 35. It's been here for decades. Years and years and years. I think back in the Obama administration, they tried to raise it to a little over $2 and Congress wouldn't have it. I mean, the AG industry and the AG lobby and Congress said, we can't make these guys pay that much. Two bucks.

Elizabeth: [00:24:29] It's so outrageous.

Carter: [00:24:30] So, yeah, so it was buck 35. It went up in a short time. It's back to buck 35 again.

Elizabeth: [00:24:36] It's gross. It's totally gross.

Carter: [00:24:38] Yeah.

Elizabeth: [00:24:39] It's just such a shame because this is all we got left and it's also kind of why we're alive.

Carter: [00:24:44] Well, yeah, to me, if I couldn't be outdoors, the quality of life would be minimal to me. I don't want to be in the concrete jungles.

Elizabeth: [00:24:57] Nor in a world where everything is just soy farms and cornfields.

Carter: [00:25:00] I grew up in Iowa. I've left there. But when I go back to visit once in a while for a class reunion or something, I mean, it's border to border corn and soybeans and the farm groves. There were hundreds of farm groves in my neck and neck of the woods that are no longer in existence. The trees have been cut down, the buildings have been burned, and all that ground is plowed under, they use Roundup.

Elizabeth: [00:25:25] Well, yeah, it's all pesticides too. So nothing's there.

Carter: [00:25:27] Actually, no Roundup treated beans and corn. The fields came up weed free, basically, so that the wildlife habitat was there. When I was a kid, there were places to hide and things to crawl into and under. Now you have this set aside, this CRP conservation ground that they pay farmers not to grow crops and leave it, depending on the contract, possibly four or five years of no growth, which creates tremendous wildlife habitat. But then when the contract ends and the farmers plow it all under. There's just nothing there any longer. So to me it's just a word. It's just criminal. When I go back and visit Iowa and just see what used to be there, that's not there anymore. It's a monoculture of corn and beans, and you grow beans because they have nitrogen fixing bacteria on the roots. So your crop rotates one year corn next year to beans next year to corn. Then if you saw the pounds of fertilizer per acre that they put on, it's just astounding. It can't be healthy.

Elizabeth: [00:26:52] No, not at all. No, no.

Carter: [00:26:56] So that's why I never went back. Once I got a taste of the mountains.

Elizabeth: [00:27:01] So now it's the nineties and wolves are coming back?

Carter: [00:27:07] Yeah, so the wolves in Montana started coming back in the mid 1980s, and I guess I rambled and forgot to say that by the 1930s, 1940s in the United States, all the wolves were killed off. They were absolutely exterminated, eliminated, extirpated, all the fancy words. Then the Endangered Species Act came along 1973, 1974. So there was just suddenly a point where it's like, we've got to stop this madness.

Elizabeth: [00:27:45] Because everything is going to be gone?

Carter: [00:27:47] I mean, you just can't keep going that way or and nothing can come back because wolves were still drifting out of Canada trying to come back here. But they were killed just as fast as they crossed into the US when.

Elizabeth: [00:28:01] When they were coming into Glacier, Were they getting killed?

Carter: [00:28:03] Oh yes. The first pack up north of Glacier was killed. Some outfitter on the Canadian side poisoned them. Then the first pack of wolves I worked with. My first experience with wolves was on the Blackfoot Indian reservation, which is just east of Glacier, right near the Canadian border. They got into trouble killing sheep and cattle, and we ended up eliminating that pack. We caught a couple of them, put them in captivity, sent them to Minnesota, and spent an enormous amount of money trying to stop the problem that wolves just wouldn't quit. So we ended up essentially killing all but one of those wolves. Then we heard a rumor: a rancher, somebody up there killed the last one. So that was their destiny. There was just no hope of them reestablishing down here until they were put under protection of the Endangered Species Act in 1974.

Elizabeth: [00:29:04] So they were put under protection but didn't actually have any?

Carter: [00:29:06] Well, there's still somebody who can fly over in an airplane and shoot a wolf from the sky and you never leave a track or a sign. There are wolves being found dead in fields that had bullet holes in them or buckshot in their back and you don't know who killed them, how do you punish somebody when you don't know who it was and so that's kind of the way it was, there was really no encouragement to expect wolves would make a comeback. But their talk started in the 1970s when I was working in Montana. I went to a lot of meetings and there was talk of re-establishing wolves. How would we do that? Well, you know, there's these plans and efforts in the 1970s and 1987, Wolf Recovery plans. Just talking about all the ways that this could happen.

Elizabeth: [00:30:08] How did that actually get passed through? Because tere were so many wolf haters at that moment, right?

Carter: [00:30:15] Well, the agriculture industry in the Western states, in all honesty, didn't want to see wolves come back. In fact, that's one of the bragging points. You could almost meet somebody in any county in Montana that would say my granddaddy killed the last dam wolf in this county back in 1932 or something. Some of them still had pictures of the guys. Then there's authors like Stanley P. Young, who wrote Last of the Loners and Last Stand of the Pack that documented those last wolf packs being killed from from the border down into Colorado. Rural America didn't see any benefit in having wolves back. But it didn't stop the scientists and researchers and wildlife managers from talking about it, especially at the federal level through the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Elizabeth: [00:31:17] Did people know what happened with Yellowstone and the biodiversity coming back and all the species coming back and when the wolves came back, was that expected?

Carter: [00:31:30] Well, I don't think any of us knew what to expect at that point in time. Through all of the research from early scientists looking at wolves and Dr. David Meech, who did his work back in Minnesota, we call it the Great Lakes region. He was one of the earliest researchers, I call him the godfather of Wolf Recovery, because he was doing this work beginning in the late 1960s. So we had this basic research foundation that knew wolves could be prolific, they could be resilient. They have a high reproductive rate, but they need space, they need food, whether it's a deer and elk, a moose, a caribou, whatever, they've got to have food to eat. They had to be, most importantly, protected. They couldn't be trapped and shot and snared. So all of that is kind of like a recipe bowl. You're out there baking in the kitchen, putting all the ingredients in the bowl. We knew what those ingredients had to be to cook up the plan to bring wolves back. But it was just a huge effort. To me, it's just unimaginable. I tell people in talks that it's like meeting the sun, moon, stars and constellations to all line up.

Elizabeth: [00:33:04] But it happened.

Carter: [00:33:06] It happened. Believe it or not, congressional people got behind it and money was appropriated to, hey, we want you to look at this and examine all the possibilities. The scientists who plugged all these ingredients into this model said, Yeah, we can do it. It's going to take money and it's going to take a concerted effort. We got to find these places. Where would we put wolves that they're not going to eat somebody's cattle, they're going to have lots and lots of room because, wolf territories are roughly the smallest ones or 250 square miles and the largest ones, if you go to up in Alaska, where caribou herds migrate and things, some of those territories are 1500 square miles. I can't begin to take credit. I mean, it's a lot of people's efforts.

Elizabeth: [00:34:13] But you had a really important role?

Carter: [00:34:16] Yeah, I had the time. Again, I always tell people I grew up my whole career. Even to this day, I'm a practitioner. I'm more of a field guy. Tell me what you want done. I can make it happen, that kind of guy. But anyway, going into the 1980s and going into their early beginning of the 1990s, people were looking at these kinds of places? So by 1994, the US Fish and Wildlife Service had a draft environmental impact statement to make wolf recovery happen. The places which were chosen were three recovery areas. One was northwest Montana, where wolves are naturally colonizing. Number two was going to be Yellowstone National Park, and number three was going to be the central wilderness in Idaho, Frank Church. We were told that this is going to get on a fast track and by 1995, we're going to be doing this. So at that time in Montana, I had helped develop the methodology to trap wolves. I became Carter, the darter, darting wolves in the lower 48 for the most part, had never happened. I'm not sure if I didn't dart the first wolf.

Elizabeth: [00:35:48] Wow.

Carter: [00:35:49] Below the Canadian border. During that time from the mid 1980s until 1995, I had trapped and helicopter captured a lot of wolves already, I had developed that skill set. The US Government Departments of Agriculture and Interior got their heads together and said, We need a wolf specialist, we need somebody to deal with this. So overnight it became this wolf specialist, and my job was to just step in and deal with livestock conflict mostly, just you're the go to guy. When wolves get into conflict with people, you go and you deal with it, which meant I had to go all over Montana and look at every dead cow calf, sheep, horse, llama.

Elizabeth: [00:36:39] Was it really crazy? Like once we're back in the picture, where people calling left and right kind of saying, hey, we have a dead sheep. Do we have a dead cow?

Carter: [00:36:48] Yes. There was this publicity that came with wolves. I call it wolf hysteria. When they talked about reintroducing wolves and they were protecting them under the ESA that everybody was thinking it was a wolf. So there's always been dead cattle laying everywhere in people's fields. But now all of a sudden. Whoa. I wonder if a wolf killed that cow.

Elizabeth: [00:37:13] Before the wolves, they weren't blaming other animals for that.

Carter: [00:37:17] Not so much, because livestock, 95 out of every hundred livestock die from non predator related causes. Digestive problems, illnesses, calving problems. poison weeds, lightning strikes and hit on the highway. All these things that kill them.

Elizabeth: [00:37:41] Right. But kind of whatever, anything that would happen, people would call you?

Carter: [00:37:46] Yeah. This wolf hysteria set in where people suddenly thought about, well, I got this dead cow, and all I read about and hear about, and people are talking about wolves, and I better have somebody come look at this. So, yeah, I had to live out of it. By then I had got divorced and was living out of my pickup truck seven days a week, 24 hours a day, going here, going there. So, I mean, I drive 300 miles one way to look at an old, rotten cow carcass that had been laying out there for months, show up and look for tracks and look for any sign that a wolf had been around. Interview people. All to say, I don't know what killed this cow, but it wasn't a wolf, because there weren't even wolves in 99% of the places I was looking.

Elizabeth: [00:38:38] Go back for one second for when the wolves first got reintroduced. Just talk about what your job was in Canada, like your role in the reintroduction.

Carter: [00:38:47] I was the second biologist on the ground in Canada in the fall, early winter of 1994 to work with the system that was set up to work with private trappers because all of Alberta is chopped up into trapping registered trap lines. So there's a trapper that has every square foot kind of spoken for up there. It's divvied up to keep people from running into each other and cause conflict and fighting and quarreling. So you get a registered trapline, only you can trap in that designated area. So to get the wolves in Canada, we had to work with registered trappers who volunteered to work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Who offered them $2,000 per live Wolf to do this. So I'd go to these guys every day with my ketamine dealers, all immobilizing drugs, my Katchpole, a noose poll, and a long syringe poll. I would just ride with them wherever they take me. So we went out in the woods where these snares were set and they had a live wolf. I would sedate it, take it out of the snare. We didn't have any kennels. When I first got up there, the Fish and Wildlife Service, I guess they were planning, but we were not prepared, neither were they, there was a lot of turmoil that just drove me crazy and I was up there to help. I wasn't up there to run the show. I was up to be an assistant. But the Fish and Wildlife Service a couple of weeks into it, said Carter. Will you take over and be the project leader? because we've got to get some semblance of organization. You're up there, right? So they'd set up contracts with pilots to come over from British Columbia to do the captures. Then it was like these guys had never darted wolves before. They were net gunners. They used nets and shot them over animals. They said, Well, you're not going to know that you're going to dart. I said, Hey, don't ask me. I said It's my understanding we're going to use darts. I have darted wolves, I have not net gunned. So we pick today in the midst of all this turmoil and day that I didn't have to go checking snares, we put together a quickie helicopter capture with the two helicopters flying tandem. We went out and I shot the first wolf of the program with these guys. We had a tough time. We talk about pilot gunner compatibility. I had to tell the pilot how I wanted to make the approach and how I could shoot comfortably out of the helicopter.

Elizabeth: [00:41:54] You would think that would just be how it worked, right?

Carter: [00:41:58] Well, it's tough. First of all, you have to remember, you have a wolf running 35 miles an hour. With any pilot when I first met him, we would talk about our jobs. I mean, his job is to fly that helicopter and be the eyes. There's a lot of skill in doing this because when I'm shooting a dart at a wolf, we're 20 feet away and you're flying in forest open country.

Elizabeth: [00:42:26] They're flying the helicopter. The wolves are running.

Carter: [00:42:29] Oh, absolutely. They're running. They're terrified. They're trying to get away. So you've got a wolf running from you. They're dodging, they're weaving, they're hiding, cutting back under you. They're making all these escape maneuvers. They probably like to tell people they probably think it's like a big giant golden eagle chasing them and they're trying to shake you. Get away from you. Then you have rotor wash, which you've got to work with the pilot, and know what angle the helicopter blades are because they can blow your dart, which is a slow moving projectile which can just blow your dart to the ground if you're fighting with the rotor wash. So when you're dating a wolf, you've got to anticipate its next move. You've got to anticipate rotor wash, you've got to anticipate the terrain. You and the pilot have to be compatible. He has to know where you want that animal position as he's chasing it. So a lot of times before I ever flew with a pilot, I would hover and we would just pick a clump of grass and I would line up comfortably with my dart gun on that clump of grass. While he was in these hovering positions and once I said right there where I needed to see, then he could line a wolf up through the bubble and know that from where it's positioned, like it's tough to grasp, that's going to be putting Carter in a circumstance where I can make a successful shot.

Elizabeth: [00:44:03] Then you dart the wolf and it goes down?

Carter: [00:44:09] It takes about 6 to 10 minutes for the wolf once it's hit with a dart to completely become immobile, where you can pick it up.

Elizabeth: [00:44:18] Then you have to run out wherever they fall and pick them up? They're big animals.

Carter: [00:44:25] Yeah. The average wolf weighs 100 pounds so you have to anticipate after that wolf is hit that we'd often guide it by if you can't hover close to it or you keep it running, you keep chasing it. So you pull away from it, you let that animal become sedated, calm down so that the drugs kick in so its metabolic rate slows down. Then you can kind of crowd it to a place that's compatible with me to get out of the helicopter, to get to that animal, because you don't want it to collapse in a rock pile on the side of a mountain somewhere. You don't end these wolves once they're sedated, you can't let them fall in water or they'll drown. So if they're running near your stream or you're near a wetland area, you have to hover over the body of water and cut the wolf off and drive him back away from the water. So there's all these things going on. The pilot's using his skill and tactics. It's important to me, he's flying and counting on you to hit that wolf.

Elizabeth: [00:45:39] When I used to think about the wolves getting reintroduced, bringing wolves down from Canada, I didn't think about any of this stuff. You just think, oh, they magically appear somehow.

Carter: [00:45:51] It's risky. The second year, we did this up in British Columbia. It was 52 below zero the first day we went out. We flew up in the mountains and it warmed up to 32 below zero. We hot fueled all day when we were in British Columbia. We never shot the helicopters off all day long and we flew tandem. We had two fixed wing spotter planes and we had two helicopters. We worked as a team all day because. If you went down by yourself out there, you would be dead. Just if you got injured at all to maintain body heat, we ended up bringing 66 wolves down from Canada, but there were two other guys that came from Alaska that darted. So there were a lot of us, there were Americans, there were Canadians, there were biologists, there were veterinarians, there were pilots, a whole mix of individuals. I was a team member.

Elizabeth: [00:46:58] It's amazing.

Carter: [00:47:00] It all worked, two years in a row it worked. We were successful in a very short time of catching these wolves, immobilizing them, taking them back to holding compounds where we went through each animal disease screening, looking for parasites on them, and sorting them. If you caught a lone wolf, the lone wolves were going to be sent to Idaho for what they call a hard release. In other words, we're going to put them in kennels in Canada, fly them down and turn them loose immediately. Open the kennel, let them run. If we caught wolves two or three that were related from the same pack, those wolves were directed to Yellowstone Park to be put in a soft release, which is putting them in one acre, holding pens to acclimate them and hold them for a couple of months before they were released. So there's a lot of data collection and a lot to keep track of so that the scientists making the decisions of where they were to be moved to would know what they were working with.

Elizabeth: [00:48:10] So from the very beginning of your time with wolves until you stopped really working with wolves directly, how much did it shift? You were always pro wolf?

Carter: [00:48:20] I became more pro wolf throughout my career because wolves have been getting a bum rap their whole life. The wolves were a competition and a pain to the European settlers. The Native tribes, it was a spiritual relationship with them and they killed them for ceremonial purposes and things like that. But, it was this European settlement where there was this intense desire to get rid of them. When we went through that wolf hysteria where people would say There's wolves around they must have killed my cow. So there's this predetermined bias that wolves in my career were getting a bum rap, because so often most of what I looked at was not wolf related. The livestock died from some other cause, very often not involving a predator at all. So more and more are just looking at what I observed day to day, week to week, month to month, year to year is that wolves sometimes they're a problem, but most of the time wolves are not a problem. So I became more and more, I guess, sympathetic to that. People are trying to make them something they're not. They're taking the fall or the scapegoat for everything else that's wrong in this country. The wolves are going to get the blame, rather than come out of this being a wolf hater or someone who really said, by God, these wolves need to die, on the contrary, that's not what I concluded after a career of working with wolves.

Elizabeth: [00:50:06] Your license plate, says Wolfer. What do people say when they see it?

Carter: [00:50:11] Yeah. I'm probably foolish to have a license plate like that, but I have a license plate on my truck, says Wolfer. Yeah, when I drive around and I've used it on contract work for different states and tribes that have helped when I pull in a gas station. Most commonly people immediately see that personalized plate and wolfer. So what does that mean? Well. I work with wolves. Well, I hope you kill the goddamn things. I said, no, no, no. I don't kill them. Well, why not? So I even explain to them that I catch them for research, I put collars on them so we can study them. They say, well, I hope you turn the cinch that collar up mighty tight, to choke them to death or whatever they suggest. I told people, Well, I said, I think we need more wolves and more places actually. So yeah, we normally get into a kind of friendly banter out there, but very seldom, if ever, do I hear a compliment about wolves, if someone asked me about my license plate.

Elizabeth: [00:51:25] No, it's true. Now in 2022, not in Idaho, not in Montana and not in Wyoming, but at least in the rest of the US, they're back on the endangered species list. The crazy thing is Idaho, Montana, Wyoming is where all the wolves live. All this wolf killing that is happening right now here, especially in Idaho, are giving bounties for $2,500.

Carter: [00:51:51] That's true.

Elizabeth: [00:51:52] To kill a wolf. Like does this ever go in a good direction or is this the end of wolves in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming?

Carter: [00:51:59] Well, when wolves were delisted in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, it was under a rider Bill. It was attached to a budget bill in the Congress. It was really underhanded, conniving, at least that's my opinion.

Elizabeth: [00:52:17] Sure.

Carter: [00:52:18] In an underhanded way to delist an animal considered an endangered species and Congress even attached a condition, no judicial review. We are delisting them and there ain't no judge, no jury, nobody is going to turn this around. So it's kind of locked in for Idaho, Montana, Wyoming.

Elizabeth: [00:52:48] What about the petition? That's with Fish and Wildlife right now, the one that's under review?

Carter: [00:52:54] That review is coming out eventually. They're reviewing the status of wolves right now. In Idaho, Montana, Wyoming i think there's like you can have an emergency re listing of the wolves I but that's going to have to mean that the wolves are against the ropes their numbers are so low that it's triggered re listing criteria. I know that sounds more complicated than it is, and it's something it's hard to convey in the short time we have to talk.

Elizabeth: [00:53:29] Right.

Carter: [00:53:31] But under emergency re-listing it could happen. But I don't think it will happen, though Montana is killing 300 plus wolves a year, Idaho is killing 500 wolves a year. We still have enough to meet the goals that were set.

Elizabeth: [00:53:55] So since you've been in this, since the Wolves first came back and you've been really in it, do you feel like is this the worst it's been?

Carter: [00:54:04] To me, it's just absolutely political, going back to my college days, you'll learn about biological carrying capacity. You take a square mile of Iowa farmland and you look at ringneck pheasants and you think, what's the biological carrying capacity? How much will this square mile support? How many pheasants, how many broods of baby chicks based on the amount of space, the amount of water, the amount of food and the territory that a pheasant family needs. Will you do that? It's the same with wolves, 250 square miles. They need that for their minimum territory with this amount of elk and deer to eat and all that, so they can grow comfortably and maintain healthy packs. A pack of wolves, have a mother and a father, a wolf. They have puppies. Then each year there's more puppies born and some of the older siblings from previous litters stay with the pack and help hunt and provide for the pups. Those packs probably operate with 10 or 12 wolves in them, packs that are continuously trapped and snared and hunted. The packs are smaller. Things are a lot more chaotic in the pack because you're killing uncle, you're killing Dad, you're killing Mom. The pups may get good leadership training and learn how to hunt, or the family could be broken up and the puppies never fully learn how to hunt. So all this hunting, trapping and things lower the pack size fragmenting them often might cause a pack to break up, and those broken packs can actually send out more wolves and more places. So all this intense wolf killing, in my opinion, it's not justified and it's unnecessary because what it's creating now, instead of biological carrying capacity, they're managed politically on social carrying capacity. How many wolves will people tolerate? They find it intolerable in rural areas.

Elizabeth: [00:56:28] Right.

Carter: [00:56:29] Not everyone. I don't want to use a broad paint brush.

Elizabeth: [00:56:33] You told me earlier, Idaho is 70% of its public lands.That's a lot of space. I know it's pretty big.

Carter: [00:56:42] That public land again belongs to everybody, but it's treated the same. So when trapping and hunting Season for Wolves opens. Now it's the state of Idaho. It's open year round. You can kill wolves year round. In some areas, you can trap and snare them year round. You have to look at the regulations because it varies between private and public lands and all that. It happened a year ago. You can kill wolf puppies in their dens. It's legal. You can even get a bounty for wolf puppies in their dens.You just have to register the kill with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, and they have to identify, collect DNA and look at these. I'm taking the extreme now. There's six dead puppies and verify it. Then that would qualify you to go to the group paying the bounties. It's a bunch of trappers that have created this. They call themselves a foundation for wildlife management. There's nothing to do with wildlife management. It's bogus. It's a bunch of guys who like to kill wolves that have designed this little program. Amazingly, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, who are in support of elk, they're donating money to this group. The state of Idaho, through the Idaho Department of Fish and Game Commission, is donating money to this. So they've got this $200,000 slush fund paying people, 2500 bucks per wolf. You bring the wolf in once you've registered this death with the Fish and Game and they write you a check.

Elizabeth: [00:58:37] It's outrageous.

Carter: [00:58:38] So it's even supported by the taxpayers of Idaho.

Elizabeth: [00:58:40] Oh, my God.

Carter: [00:58:42] It's spreading to Montana. Now I hear a friend of mine, a colleague, called me two days ago and said, they're trying to get this bounty system into Wyoming too.

Elizabeth: [00:58:52] Oh come on really?

Carter: [00:58:53] Oh, yeah, it's trying they're trying to get it to catch on all over.

Elizabeth: [00:58:56] So how do you deal with all this?

Carter: [00:58:59] I was flabbergasted to hear about these bounties because this bounty system started out on a much smaller scale, but I think in 2012, perhaps so it's been around a while, but it's gaining momentum and with the politicians behind it. Freely handing out the taxpayers money and then the Fish and Game Commission handing out sportsman's money. It's all kosher. I protested when I first heard it, I said that this can't be legal. Well, the attorney general says, Yeah, I guess they'd run it up the ladder and it is legal to do this now. I heard Fish and Game on. Some of their media reports say, hey, the wolf hunters and trappers are our first line of defense, to keep their numbers down. Well, so they kill 100 cattle out of two and a half million and they kill. 100 sheep out of a state population of 300,000 sheep. Do the arithmetic. Right now, they're causing damage to the tune of 0.04 or something like that. Right, I'm not minimizing it through my whole career. I mean, it's if a wolf kills livestock. Ranchers take it personally and it hits them in their pocketbook.

Elizabeth: [01:00:35] Except they get reimbursed.

Carter: [01:00:36] They're being reimbursed in most states where there's wolves, there's compensation programs that cover that cost. Defenders of wildlife paid it for years, right up until delisting and now there's federal money and state money to cover the losses and to try and just simplify it. In Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, there are pretty much, I will say, statewide herds of elk, there are as many today as 26 years ago when the wolves were reintroduced.

Carter: [01:01:15] The population overall is in great shape. Montana, Idaho and Wyoming, where we have this intense wolf killing. Certainly they eat elk, the average wolf will kill from 12 to 22 elk size animals per wolf per year.

Elizabeth: [01:01:35] Well, also, you're talking how many wolves are in this country? 2000.

Carter: [01:01:39] Oh, Idaho, 5500.

Elizabeth: [01:01:42] So they can't kill that many elk anyway because there's just not that many of them.

Carter: [01:01:46] Wolves killing elk is good. They call out the sick, the weak, the inexperienced, the injured. They will get those first because they're the ones that can't run as fast and escape as well. They call the herds if you talk to people who are skilled in elk science, elk get older, they become non productive. It's just like farmers, ranchers who have cattle. Each year they call them the pregnancy test. The old girls who aren't producing go to McDonald's or wherever they go. Well, wolves do the same things. Studies show that wolves select for the old and the infirm. But the hunters, human hunters, kill what walks in front of their guns. In a lot of states, they allow antler less hunts for calves and for cows. So if a cow elk walks out in front of your rifle scope and you shoot, you have no idea how old that elk is. The studies show that hunters generally are killing younger age class of elk, the very productive cows, the ones having calves every year. But the wolves

Elizabeth: [01:03:09] Are killing the old.

Carter: [01:03:10] The studies around Yellowstone, the wolves are killing the older elk who may not even have a calf, but they're out there competing and eating grass. So what wolves do is beneficial.

Elizabeth: [01:03:25] It's what they're supposed to do.

Carter: [01:03:26] Yes. Its the way the system works.

Elizabeth: [01:03:29] Is there anything that can happen like that that can change all this?

Carter: [01:03:34] Well, we're in a culture that started with settlement, I mean, hunting tradition, if there's anything surplus, kill it. You even learn that in wildlife management in college, you try to look at the peaks, the populations high, and you look at the troughs where the population's low. Humans want to kind of manage them on a straight line part way between the peak and part way between the trough and make it for human use. So this is what you're dealing with, a culture that by God, my granddaddy and my great granddaddy, we all hunted. They hunted. It's kind of this system that's been here for a long time and nothing much changes. Nor are the people in charge going to let it change. Whose side of my honor. I mean, it sounds like I'm 100 and a trapper my whole life and a fisherman more or less, too. But I think as this country changes, there's got to be more people sitting at the table and hunters, trappers and fishermen, because there's a tremendous industry out there that bird watches, that millions of dollars spend in places like Yellowstone Park.

Elizabeth: [01:05:01] Oh, so many people go to Yellowstone in hopes of seeing a wolf.

Carter: [01:05:05] There's outfitting groups. There's people whose business is to take tourists wolf watching and looking at all the other wildlife around the park. This year, just to add a little more salt to the wound, I believe the last count between 24 and 29 wolves from Yellowstone Park were killed this winter.

Elizabeth: [01:05:29] It's like 30%, right?

Carter: [01:05:31] Yeah. Of that population, there's about 100 - 220 wolves in the park.

Elizabeth: [01:05:41] 20, 25%.

Carter: [01:05:42] Yeah, it's pretty, pretty high.

Elizabeth: [01:05:44] A huge percent, though.

Carter: [01:05:45] Yeah, there's been a lot of letters written and there's biologists and scientists have written letters calling this absurd. You've got businesses all around Yellowstone like hotels and motels. People who do safaris or whatever you want to call this, taking tourists out, their business are being killed by, and why? Why kill park wolves? Well, the governor of Montana, I mean, he just said, hey a wolf is a wolf and when I say in the park, it's in the park. We're on the south side of the park. It's fair game, period. So that's the politics right now is to kill wolves. That's what's going on.

Elizabeth: [01:06:38] I'm sorry. It's horrible.

Carter: [01:06:41] Yeah. I've never killed a wolf for sport. Nor would I ever consider it. I have handled hundreds of live wolves. For me to kill a wolf would be like, shoot my dog.

Elizabeth: [01:06:57] Yeah.

Carter: [01:06:57] No interest whatsoever in that.

Elizabeth: [01:06:59] Carter, thank you for this. You're amazing. Thank you so much. To learn more about Carter and to learn more about wolves and what we can do to help them go to our website, SpeciesUnite.com We will have links to everything. We are on Facebook and Instagram at @Speciesunite. If you have a spare minute and could do us a favor, please subscribe rate review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts really helps people find the show. If you'd like to support Species Unite, we would greatly appreciate it. Go to our website, SpeciesUnite.com and click Donate. I'd like to thank everyone at Species Unite, including Gary Knudsen, Caitlin Pierce, Amy Jones, Paul Healey, Santina Polky, Bethany Jones and Anna Connor, who wrote and performed today's music. Thank you for listening. Have a wonderful day

Become a Species Unite member!

You can listen to our podcast via our website or you can subscribe and listen on Apple, Spotify, or Google Play. If you enjoy listening to the Species Unite podcast, we’d love to hear from you! You can rate and review via Apple Podcast here. If you support our mission to change the narrative toward a world of co-existence, we would love for you to make a donation or become an official Species Unite member!

As always, thank you for tuning in - we truly believe that stories have the power to change the way the world treats animals and it’s a pleasure to have you with us on this.